The Trojan War: An Introduction

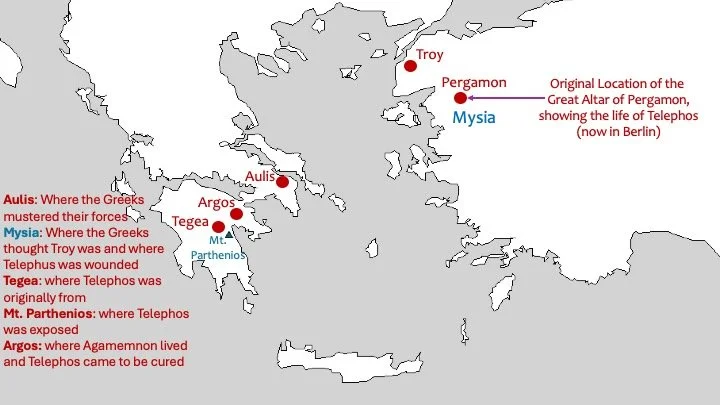

The Trojan War was the last great event of the Greek mythical storyworld. You might know, from movies and other media, that the Greeks went to war against the Trojans over the seduction of a drop-dead gorgeous woman named Helen, who famously launched a thousand ships to get her back. It was a ten—or twenty—year war that caused great suffering and losses on both sides. In this episode, the first in our series on the Trojan War, we give an overview of the war, a bit about our sources, and other conflicts in and around Troy, including Heracles’ sacking of the city and the Greeks’ attack of Mysia to the south while thinking it was Troy. To orient you, here is a map of the locations mentioned in the podcast.

The Trojan War that we’re talking about in this series is the second war the Greeks waged against Troy. The first was when Heracles destroyed the city after the king, Laomedon, failed to pay him for saving his daughter, whom the king was forced to set out for a sea monster in return for his failure to pay the gods for building the mighty walls around the city. Heracles came back to the city later, sacked it, killed Laomedon and most of his sons, and handed over the city to the youngest, once named Podarces but later Priam, who is still king in the more famous Trojan War. Here are the connections between the first sacking of the city by Heracles and the later one by Agamemnon and company:

Hesione, the woman Heracles saved, was given to Telamon (brother of Peleus) and bore to him Teucros (Teucer), who was a famous archer in the second war. His half-brother, Ajax the Greater (see episode 28), was son of Telamon and his legitimate wife Periboia.

When Heracles died in a very tragic way, he bequeathed his bow and arrows to Poias, who in turn bequeathes the bow and arrow to his son Philoctetes, one of the Greek fighters at Troy. Philoctetes has his own story, but it’s prophecied that Troy cannot be taken without the bow of Heracles. Philoctetes will kill Paris, the instigator of the whole mess.

Priam is the king of Troy and the only one to see Troy sacked twice.

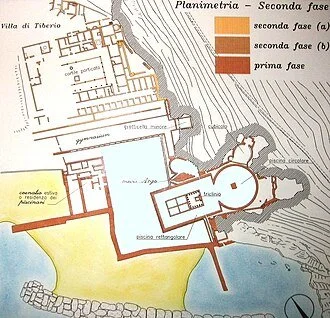

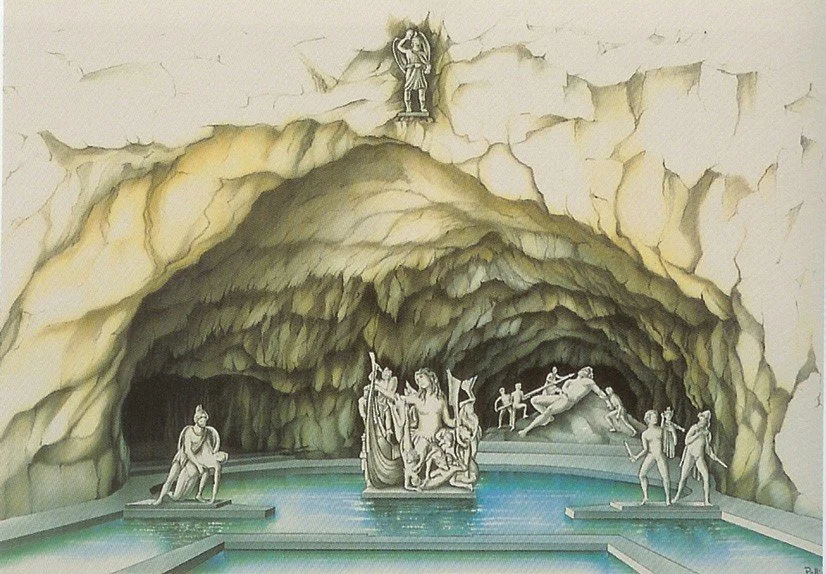

The story of Hesione is a doublet of the story of Andromeda. By “doublet” we mean a myth that shares specific details and motifs. Here, each woman is set out on a cliff to die by a father who offended the gods (or whose wife did so). Each woman is saved by a Greek hero who happens to be passing by. The similarities can cause confusion. In the ancient villa of the emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD) there is a statue of a woman who is positioned as someone set out on a cliff. The label in the museum says “Andromeda” but it is certainly not her, but Hesione. Why? Because all the other sculptures are from the Trojan War. Here is the statue:

The villa of Tiberius was from the period of the republic purchased and remodeled by the emperor, who was fond of mythology. He even had scholars of myth attend his dinners and he’s ask them tough questions about mythology. Famously, the cave mouth had a partial collapse as the emperor was dining on the podium in the middle of the water and was barely saved by one of his henchmen!

Sculpture locations: Zeus abducting Trojan Ganymedes at top, Odysseus blinding Polyphemus in the back right, Scylla destroying Odysseus’ men in the center, the so-called Pasquino group (showing either Menelaus carrying body of Patroclus or Ajax carrying Achilles) to the left, and Odysseus and Diomedes stealing the Palladion from Troy on the right. Hesione would surely have been set into the rock face above the cave as well.

The first attempt to take Troy was very problematic—exemplifying how messed up the war was. The Greeks had no idea where Troy was, so they attacked Mysia, thinking it was Troy. Their champion, Telephos, staved off the Greeks for a while but was eventually wounded by Achilles. He was something of a local hero, and it was his mythical story (told in the podcast) that the Attalid dynasty clung to when they built the great Altar of Pergamon, which has some of the most stunning sculpture from the Hellenistic period. Here is a picture of the whole as it is presented in the museum in Berlin

The Great Altar of Pergamon (as reconstructed in Berlin). The lower sculptural program shows the Olympian and other gods fending off an attack of the Giants (children of Gaia). The upper reliefs about Telephos are in a separate location.

The Telephos reliefs at the Pergamonmuseum in Berlin. The central panel (above and right of the smaller display in front) shows Teuthras, the king of Mysia, finding Auge deserted on the shore.

The healing of Telephos by Achilles is found in a number of ancient works of art, but my favorite is from the so-called house of the Telephos Relief in Herculaneum.